Could the Stomach be the Cure to Schizophrenia?

By Sara Green

Schizophrenia is a word recognized by many, but understood by few. Schizophrenia, or SCZ for short, is a chronic brain disorder characterized by psychosis that occurs in both men and women. Symptoms include hallucinations, delusions, disorganized speech and thoughts, and lack of motivation. Men often experience initial symptoms in their late teens or early 20s, while women show first signs of illness in their late 20s and early 30s.

Approximately 1% of the population is affected, making it one of the top causes of disability worldwide [1]. It causes a two to three-fold increase in death and can be an extremely debilitating disorder. Unfortunately, there is no cure to the disorder - yet.

Recent developments in microbiota research have suggested possible treatments that could significantly improve the quality of life for affected patients. Inulin, a type of dietary fiber, has been studied as a possible treatment for schizophrenia.

What causes Schizophrenia?

The underlying mechanisms that cause Schizophrenia are very complex. Not only do genetics play a part, but social and environmental factors can make a person more likely to develop the condition as well [2]. Without a clear understanding of what causes schizophrenia, treatment options have been extremely limited. In recent years, the scientific community has put more focus into developing alternative treatments to the disorder. One such focus has been on the gut microbiota and its relationship with the Central Nervous System (CNS). The role of the “microbiome-gut-brain (MGB) axis” could be essential in managing the symptoms of schizophrenia.

What is the gut microbiome?

Who would have guessed that your stomach can affect your brain? Your gut is the host of a party for microorganisms, mainly bacteria, that are collectively called the microbiome. Each microbiome is unique; the types of bacteria in your gut differ in many ways from the bacteria in someone else’s. Your microbiome is also always changing. Diet, medication, age, and disease can alter the composition of bacteria in your gut.

Picture the microbiome like a party in your living room. The members of the party may come and go depending on the environment. The more people you have in your party, the more fun it will be. Sometimes the party can run smoothly, and at other times, it can ruin the rest of your house. The microbiome has the same effect on different parts of your body. It contributes to the function of your immune system, endocrine system, and nervous system [3].

What is MGB?

So, is the saying “you are what you eat” true? It could be. The microbiome-gut-brain (MGB) axis is the connection between the gut microbiota and the brain. It lets the brain and the gut microbiome communicate bidirectionally.

When your microbiota are thrown out of balance they enter a state called dysbiosis. Dysbiosis promotes systemic inflammation, an immune response that can affect brain function - in a bad way. It has been linked to cognitive and behavioral effects [3].

Considering the interconnectedness of the microbiome and the inflammatory response, it seems very possible that the gut microbiota could contribute to the development of brain disorders. This is precisely what researcher Li Guo set out to investigate in regards to schizophrenia.

Diagram of the microbiome-gut-brain axis connection [5].

Is Inulin the savior?

Inulin is a type of dietary fiber linked to several health benefits. It is shown to regulate the immune system, metabolism, and balance the gut microbiome. Inulin is considered a “prebiotic”, meaning it helps the good gut bacteria grow. Inulin’s beneficial effects don’t stop there; it is also shown to stimulate the immune system to release anti-inflammatory responses. Could inulin improve schizophrenia by modulating the gut microbiome and suppressing inflammation via the MGB axis? Dr. Guo’s team set out to solve just that.

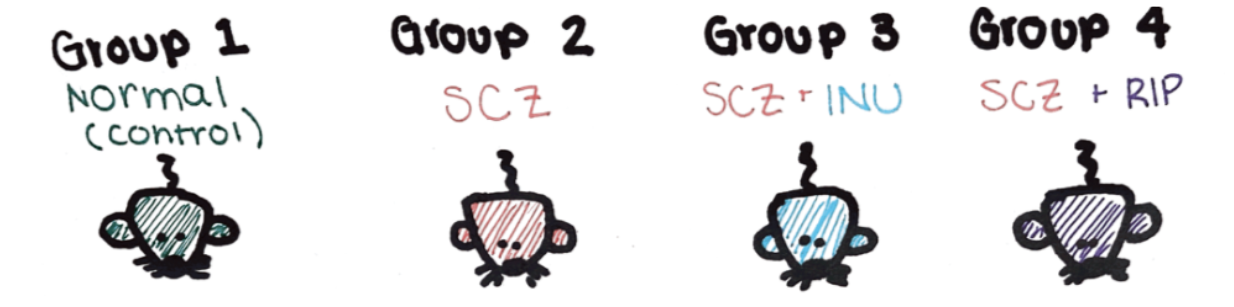

In the study, sixty mice were divided into groups to test if inulin could alleviate symptoms of schizophrenia. Three groups of mice with schizophrenia were tested, as well as one group of unaffected mice. The first group did not receive any inulin, the second group received inulin, and the third group received risperidone (a drug used to treat schizophrenia).

The control (normal) and experimental groups used to compare the effects of inulin treatment on schizophrenia symptoms.

After 6 weeks of treatment the mice were subjected to behavioral tests. To study anxiety levels, mice underwent open-field tests (OFT) in which mice were placed individually in the middle of an empty arena and allowed to explore freely for six minutes. The total traveled distance was used to measure locomotor activity, which indicates increased learning and motivation. Rearing (childcare) and going to the bathroom were indicative of “anxiety levels” to study if inulin may regulate anxiety and depression.

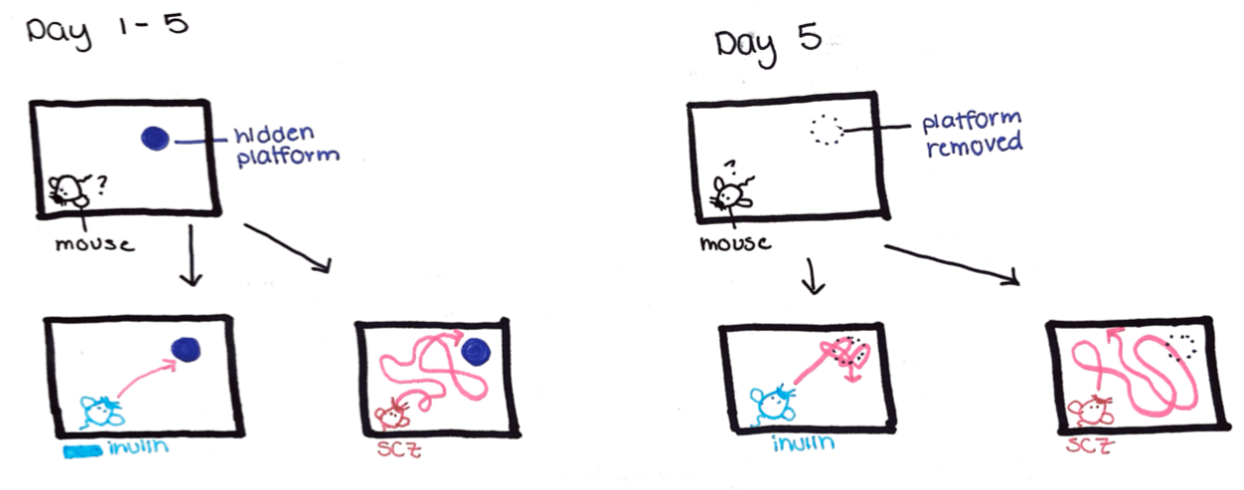

To test cognitive abilities, mice were subjected to morris water maze (MWM) testing (figure 1). In this test, mice were put in a corner facing one of the walls of the maze. For the first four days of testing, mice were given 60 seconds to locate a platform in the middle of the maze. Faster location translated to increased learning memory. On day 5, researchers removed the platform and monitored the number of times the mouse crossed the area where the platform used to be. The more times a mouse crossed the platform area, the higher their spatial recognition memory was.

Blood tests, intestinal tests, brain analysis, and DNA analysis were done to study changes in mice immunity and microbiota [4]. Researchers were hoping to see less inflammation and neuronal death in mice treated with inulin. They also hoped to see more diversity in the gut microbiome, indicating less dysbiosis. If mice treated with inulin had decreased inflammation, neuronal death, and dysbiosis, this would indicate a connection between the gut and brain.

What were the results?

Results were promising; they revealed inulin alleviated schizophrenia-like symptoms in mice. Mice treated with inulin performed better on both the behavioral tests (OFT and WMW). In the OFT test, untreated schizophrenic mice showed less activity and rearing behavior, indicating depression. Promisingly, mice treated with inulin had a significant increase in number of rearing and total distance. These results reflect that inulin may regulate symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Inulin treated mice also performed better in MWM tests, taking significantly less time to find the platform location than untreated mice. Once the platform was removed, treated mice crossed the platform a greater number of times. These results reflect an increased learning memory and spatial recognition memory in mice treated with inulin.

Diagram of Morris Water Maze (MWM) testing. Days 1-5 show that inulin treated mice locate the platform faster than schizophrenic mice. Day 5 shows that after the platform was removed, inulin treated mice crossed the area more frequently than schizophrenic mice.

Brain, immune, and gut studies supported this improvement in behavior. Mice treated with inulin had significantly less inflammation and brain cell death. Furthermore, RNA analysis of the gut microbiome showed that inulin treatment restored gut dysbiosis. Certain “good” colonies of bacteria increased, while other “bad” gut bacteria decreased. Ultimately, inulin treatment caused improvement in all tests, indicating that it can relieve symptoms of schizophrenia.

So… what?

So is inulin the next frontier of schizophrenia treatment? By modulating the gut microbiota, inulin prevented inflammation and brain death via the MGB axis. This reduced several symptoms consistent with schizophrenia. Future research is needed to confirm and elaborate upon these results, but the future is promising.

On a greater scale, this study provides insight into the close connection between the gut microbiome and the brain. The MGB is a new frontier for the treatment of mental illness, and understanding the beneficial effects of diet on the MGB will provide new approaches for treatment. Moral of the story is, don’t underestimate the potential effects of the party in your stomach!

References

McGrath, John, Sukanta Saha, David Chant, and Joy Welham. “Schizophrenia: A Concise Overview of Incidence, Prevalence, and Mortality.” Epidemiologic Reviews 30, no. 1 (November 1, 2008): 67–76. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxn001.

“What Is Schizophrenia?” Accessed February 9, 2022. https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/schizophrenia/what-is-schizophrenia.

Petra, Anastasia I., Smaro Panagiotidou, Erifili Hatziagelaki, Julia M. Stewart, Pio Conti, and Theoharis C. Theoharides. “Gut-Microbiota-Brain Axis and Its Effect on Neuropsychiatric Disorders With Suspected Immune Dysregulation.” Clinical Therapeutics 37, no. 5 (May 1, 2015): 984–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2015.04.002.

Guo, Li, Peilun Xiao, Xiaoxia Zhang, Yang Yang, Miao Yang, Ting Wang, Haixia Lu, Hongyan Tian, Hao Wang, and Juan Liu. “Inulin Ameliorates Schizophrenia via Modulation of the Gut Microbiota and Anti-Inflammation in Mice.” Food & Function 12, no. 3 (February 15, 2021): 1156–75. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0FO02778B.

Doug Cook RD. “The Gut Brain Axis. Your Ally for Better Health,” August 31, 2017. https://www.dougcookrd.com/gut-brain-mental-health-dietitian/

Chang, Lijia, Yan Wei, and Kenji Hashimoto. “Brain–Gut–Microbiota Axis in Depression: A Historical Overview and Future Directions.” Brain Research Bulletin 182 (May 1, 2022): 44–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresbull.2022.02.004.

Sara Green (‘22) is a Senior at Bucknell University and will graduate with a B.S. in Biology while on the Pre-Med track.

At Bucknell, I spent two years as secretary of the Pre-Health Society and was elected President my senior year. I volunteered at the Community Harvest Meal Program and Miller Center after school program, and contributed to philanthropy projects as a member of the Delta Phi Chapter of Kappa Kappa Gamma.

During the Summer of 2021 I worked as a research assistant for The Breast Cancer Research Foundation (BCRF). This experience allowed me to explore several novel projects that aim to improve Breast Cancer treatments worldwide.

After Bucknell, I will work at Brigham and Women’s Hospital before pursuing medical school. At BWH I’ll work as a clinical research coordinator, assisting in a project that aims to find early blood biomarkers of Breast Cancer in hopes of improving early detection.